Historical Growth of Landfill Gas Projects in EPA LMOP Dataset

EPA’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP) dataset is a foundation of the transformation of negative methane emissions into beneficial use of biogenic natural gas. This transition is robust, dynamic, and well documented. It has always been the older sibling to the farm digester AgStar dataset discussed in the earlier post, Cultivating Fuel on Farms and the Growth of the US Farm Digester Industry. Biomass Rules has relied on both datasets for promotion of biomass opportunities since they became available many years ago.

The expansion of the smaller farm digester methane utilization data is only just beginning to bring these two very different sets of data into a comparative context.

Methane in the traditional sense is defined culturally and politically as a negative emission into the environment. Chemically speaking, methane is the compound of value in natural gas, so from the beneficial perspective, methane is known as natural gas when there is value. This labelling becomes more complicated when considering additional fossil carbon when burning fossil natural gas, and recycling already available atmospheric carbon in biogenic, renewable natural gas (RNG). RNG is still primarily methane as a chemical. But it allows atmospheric carbon in methane (CH4) to substitute for fossil carbon in traditional natural gas (CH4) creating an offset value.

Landfill gas is an unexpected product of the dry tomb technology encouraged in the statutes and regulation of municipal solid waste (MSW), or trash. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, 1976, set up the infrastructure to prevent random dumping of MSW. Landfills began as sanitary repositories for festering human waste. In the 1970s, it was easy to contain the emissions we could see like trash and manure. It was not until later that it was understood that methane gas formed, collected, and escaped in quantities that were troubling on a large scale. The landfill gas capture initiatives were developed as a remedy to leakage from this very successful MSW technology adoption.

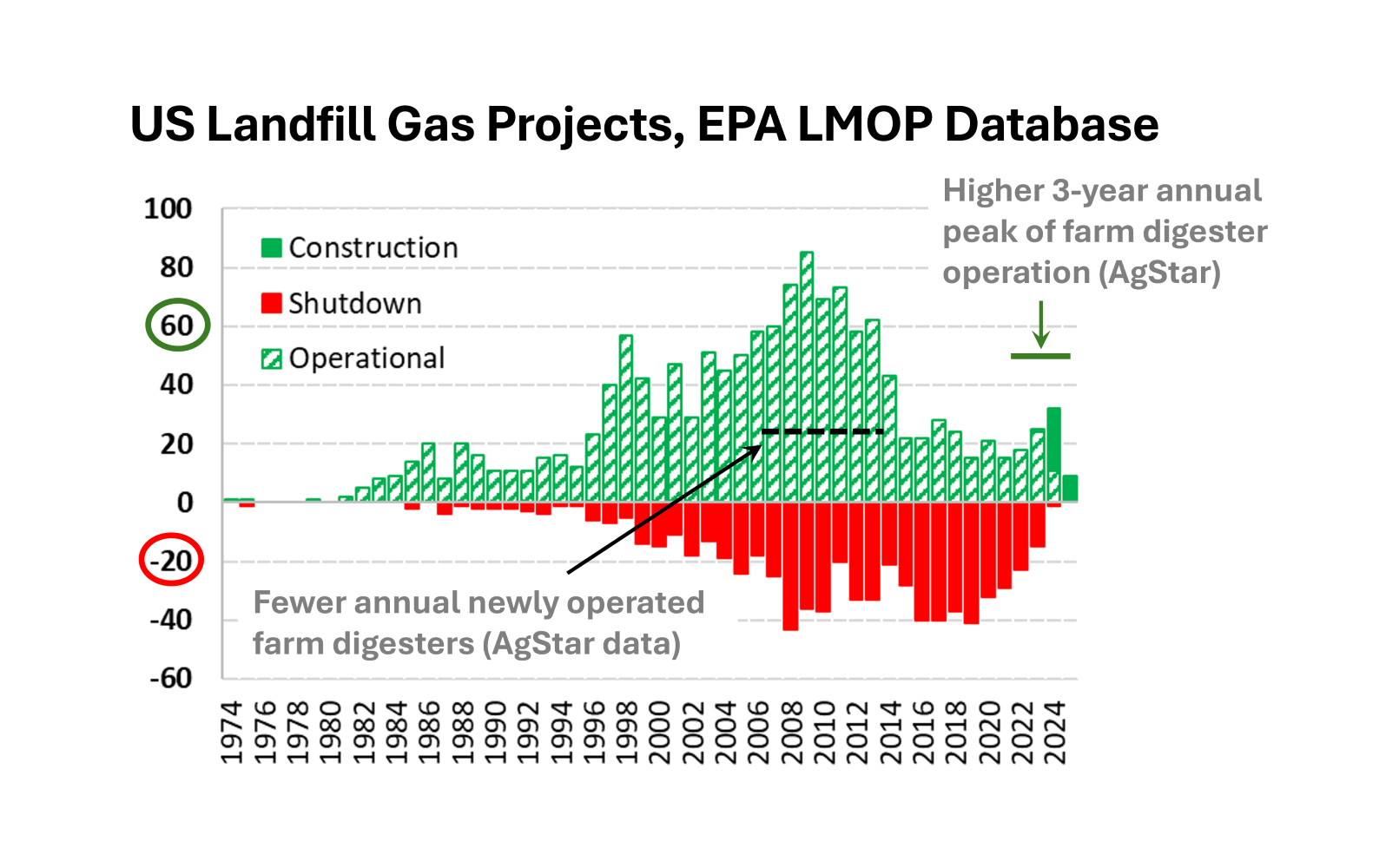

The first thing of note in the 50 years of landfill gas projects is that early on, landfills began adopting gas collection projects. In both number of projects and size of methane capture, these biogas systems dwarfed farm digester projects. Landfill gas projects increased annually to a high of 80 projects in 2008. At the same time, the smaller farm digesters were adding about 20 projects per year. It is also interesting that even when the rapid growth of landfill gas projects dropped off, they still added 20 projects a year (historical digester additions).

Just as the growth of landfill gas projects has been greater than farm digester projects, so has the number of projects that have been shut down. The landfill gas projects, like farm digesters, are byproduct development enterprises. This means that the success of the gas development project is determined by the success of, in this case, landfill. Evolving regulations and technologies also add to the success of these projects. At first glance, it appears that there are a lot of gas projects that shut down after the turn of the century, 2000. Relative growth can be seen by comparing the number of annual projects shutdown to those that are started. In the first decade 40 percent of landfill gas projects shut down compared to those that were started. This is close to the same ratio of annual average of farm digesters shutting down to those starting up.

The pattern between landfill gas projects and farm digesters over the last 25 years has been very different though. Some comparative digester metrics have been superimposed on the landfill gas project data chart in this post. The peak startups for the farm digester data are highlighted on the vertical axis in a green circle. The peak shutdowns for the farm digester data are highlighted with a red circle. Again, the digesters are a smaller number with generally smaller biogas production than landfills.

The major differences are the shifts in the last 10 years. Over the last decade, beginning in 2015, the landfill gas projects that were shut down were greater than the number of new projects started. This is just the opposite of the same factors in the farm digester data. Farm digester startups spiked for the last three years of data (2021, 2022, and 2023), while at the same time the near-term projects that shut down were nearly zero.

Fascinating traditionally confounding dimensions of this emerging RNG industry include:

- Both the landfill gas project industry and the smaller, but growing farm digester industry, are the result of incomplete waste treatment technologies (landfills and lagoons). In the 1970s, methane escaping into the atmosphere was not viewed the same as it is today.

- Combining the remediation of solid waste (trash) and liquid organic waste (manure) emissions have created both 1) an offset value and 2) a transportation fuel monetary value to shift the economy in beneficial ways.

- Over the last 50 years, segments of the solid waste stream have been gradually removed from landfill inflows. One of those segments of value has been organic solid waste (which is the feedstock for landfill gas methane). Used paper has been recycled for decades or composted. Today much of the food waste flow of MSW is moving into stand-alone digesters, which yields greater methane production than burying it in a landfill.

- Capturing landfill gas is still a great investment in solid waste treatment. But as this historical data shows, the highest yielding projects have been completed.

- MSW diversion technologies (and industries) are still growing. Farm liquid organic waste development in digesters, and now, food waste diversion digesters, are a growth frontier for the RNG industry.

- Organic waste is not automatically a methane offset. In the 1960s, egg layer manure was treated as a liquid manure and anaerobic lagoons. Today, it is treated as dry manure without adding wash water or bedding. Composting or gasification is still a best use of dry solid organic waste. Digesters will be most efficient for more liquid organic wastes. A point is that digesting wastes may create more methane than would have occurred in composting them. But as the resulting methane has economic value and is destroyed with use, this is a good thing.

The biogenic methane RNG gas industry has been under development for 50 years. It has been a long time in coming. Current RNG markets have been driven by the collective demand for waste treatment, environmental remediation, fossil energy offsets, and monetary benefits of transportation fuel. No single demand was sufficient to deliver but combined, they have become an economic force. This was also an iterative process, of learning to treat waste, operate multiple sequential technologies, and adapt the refined emissions into products with a market demand. It has simply taken 50 years. But it is a bright hope in today’s energy portfolio.

Comments

Historical Growth of Landfill Gas Projects in EPA LMOP Dataset — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>