The Economics of Food – It is Just A Little More Complicated

Hemp seeds command a premium price. USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) now reports weekly hemp product prices. In the September 11, 2024 report, one pound of hemp seeds was reported at $12.64. That is down from $14.39 per pound the week before. The farm price of peanuts in the same time period (Sept 13, 2024) was reported to be $0.27 per pound.

This is like comparing apples and oranges, right?

It is inappropriate to compare farm-gate prices like the above peanut price with the processed hemp seed prices (retail grocery). Different market levels as discussed in the Seminole Role of Commodities in Food Value blog, work differently. The title of today’s blog is inspired by Patrick Westhoff’s brilliant book, The Economics of Food (Pearson, 2010). Food economics is never as obvious is it appears.

To illustrate, prices for peanuts, sunflower seeds, almonds, and hemp seeds were pulled from Walmart’s Website. One sample is not a statistically viable for research purposes, but it will work to illustrate the complexity of food value. On September 16, 2024, Walmart reported product prices that convert to dollars per pound ($/lb) at the following values:

- Great Value Roasted Peanuts $2.30/lb.

- Great Value Roasted Sunflower Kernels $2.48/lb.

- Great Value Dry Roasted Almonds $6.15/lb.

- Manitoba Harvest Hemp Heart Seeds $10.97/lb.

The first thing to note is the farm price for peanuts is $0.27 per pound and the retail grocery (processed) peanut price is $2.30. It works like corn and corn cereal in our U.S. food marketing system.

It was remarkable that comparing the nut labels on calories, serving size (grams), fats (grams), protein (grams), carbs (grams), and sodium (milligrams, mg). Looking at the actual amounts, or absolute values, it is helpful to make dietary choices. But for our purposes, a cross-comparison of differences is the most meaningful.

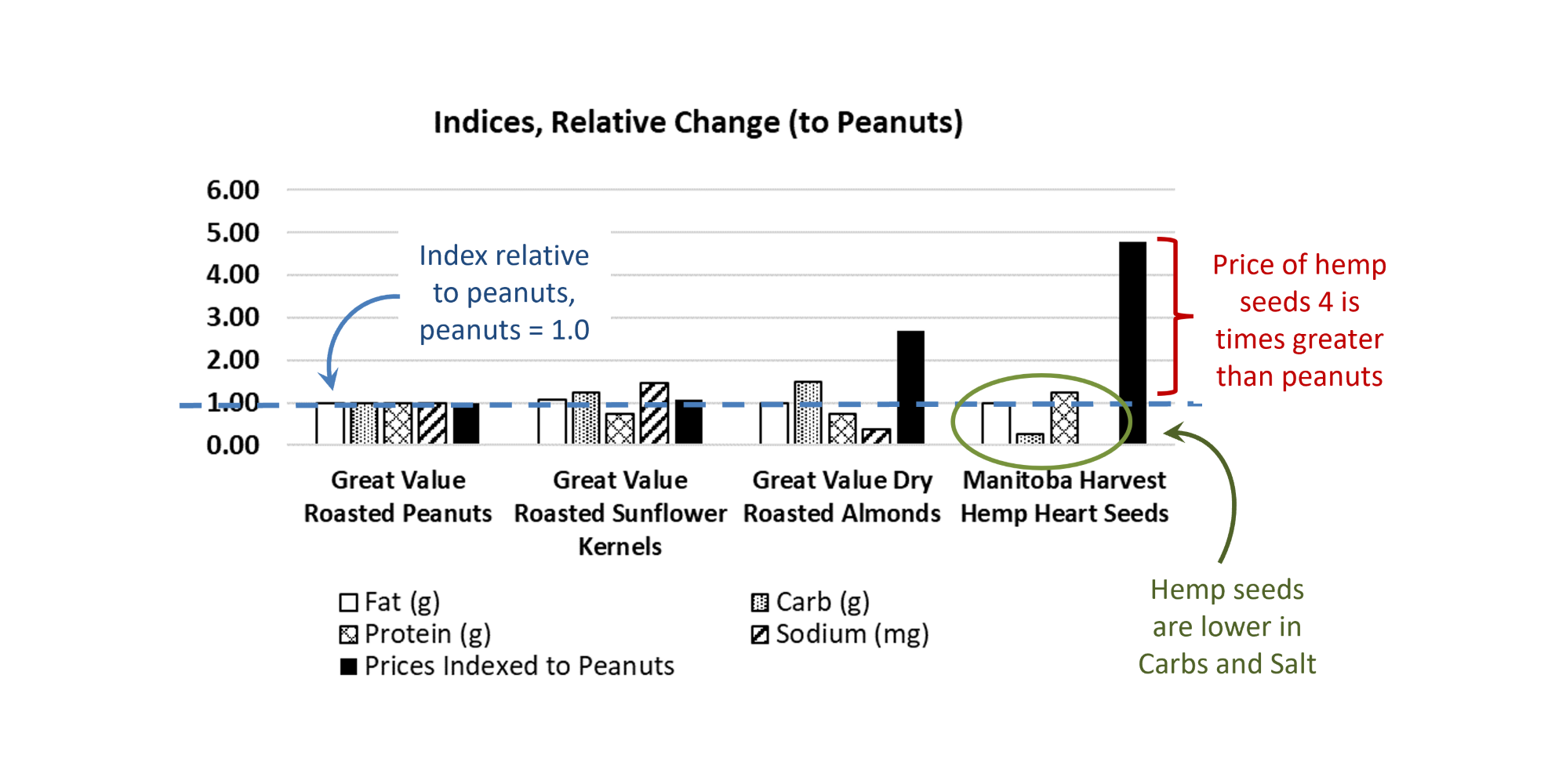

Assigning dry roasted peanuts as a standard, we can divide all the value by the representative value of peanuts. All the other products are indexed to peanuts and highlights the marginal differences between each product. This works even though the units differ. The chart shows each parameter relative to peanuts.

The indexed item, peanuts, is already factored into the other indexed values. But is also presented separately in the chart to make the point that dividing each of the components of dry roasted peanuts by the same values equals one. In this example, there is almost no difference between dry roasted peanuts and sunflower seeds.

The fats, protein, carbs, and sodium in almonds vary a bit from peanuts and sunflower seeds. The value of roasted almonds is two times greater than peanuts.

Hemp prices are four times greater than peanut prices in our example. The hemp seed product sold by Walmart reported zero sodium. That is impressive. Also, very low carbs per serving.

What do these different prices have to do with food inflation?

Nothing. Our example compares across commodities at a single point in time. Inflation deals with prices changes over time.

A greater challenge is that economic theory is based on maximizing benefits over costs. On a simple dollar-basis this infers that peanuts are maximized benefit for the cost. Everyone should be buying peanuts.

The actual conditions for economic efficiency are:

- Undertaking an economic action is efficient if it produces more benefits than costs.

- Undertaking an economic action is inefficient if it produces more costs than benefits.

The factors compared here, are the items in the nutrition label on each product. Our initial assumption is that all the benefits and costs are contained in the reported nutrient and dollar values on each product.

Product labels are regulated. Product manufacturers are complying with the regulation in the label, this is why each item is standardized. These labels serve a benefit and if a consumer’s individual nutritional components are out of balance, the label information may also serve as a cost.

Each of these four products have industry promotion groups. According to the individual product promotion group, their own product alone is the best value for the consumers.

There is some uncertainty about whether each industry promotion group is an unbiased source of information. The economy works best with perfect information. But when unknowns are present there is incomplete or imperfect information.

In the case of hemp seeds, there is a lot of imperfect information. As mentioned previously, I worked farm produced industrial hemp nearly 30 years ago. A summary paper I wrote in the late ’90s that I thought was unbiased and objective was heralded as both ammo to move the issue forward – and at the same time by different groups – ammo for stopping the effort.

Even today, in 2024, there is a great deal of controversy about the benefits and risks of any cannabis sativa product. For hemp, the lack of consensus makes it a bit of a rebel food product. The consumers who are paying $11 to $14 per pound for hemp seed are convinced that the benefits outweigh the costs. For these consumers, the benefits DO OUTWEIGH THE COSTS. It is an economically efficient choice.

This is possible because of the efficiency of the U.S. food marketing system, not the opposite. Traditionally, benefits and costs are most easily measured in dollars. But today’s consumers are not only concerned with the least-cost choice. And, yes, it is wonderfully complicated.

Biomass Rules loves the utility, and low cost, of dry roasted peanuts, but we embrace the power of choice U.S. consumers enjoy.

Comments

The Economics of Food – It is Just A Little More Complicated — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>