Local, the Uneasy Substitute to Global

As a quantitatively trained, free-market economist, I had been shaped to believe buying ‘local’ was a preference that was not cost-effective. But as I grew into a manure visionary and biomass systems economist, bulky and wet materials of limited value were known to be costly to transport any distance. Local market constraints become more real. Manure systems are often engineered to use water as a carrier for safe and inexpensive movement across a facility. Hauling manure out to the field, all that beneficial on-site water transforms into freight with added costs. Biomass energy systems work the same way. Hauling bulky bales of corn stalks or miscanthus shorter distances cost less. Local has efficiencies.

The competitor of the local market is the global market. US farm commodities are exported all over the world. The US imports significant high valued food items like chocolate, coffee, and wine. Imports and exports work well because they allow the lowest opportunity cost producer to leverage that advantage over countries where the opportunity cost of production is higher. That drives trade and commerce, and it works domestically as well as internationally. For such a simple concept, it gets confusing very quickly. It does not help that the term ‘trade’ in the international sense can mean the sum of exports and imports.

In 2018, the US took a position of protecting US products and producers from inequitable tariffs. Trade wars ensued and they have not actually gone away. But for about five years, there were trade wars, international crude oil price wars, a pandemic, post-pandemic supply chain stoppages, and an actual war in eastern Europe. Teaching economics is always more interesting when the global economy is on fire. Thinking the globalization contraction began in 2018 made sense to me. But a fall 2022 article in the Wall Street Journal pointed to World Bank data that inferred a trade contraction began in the financial crisis of 2008.

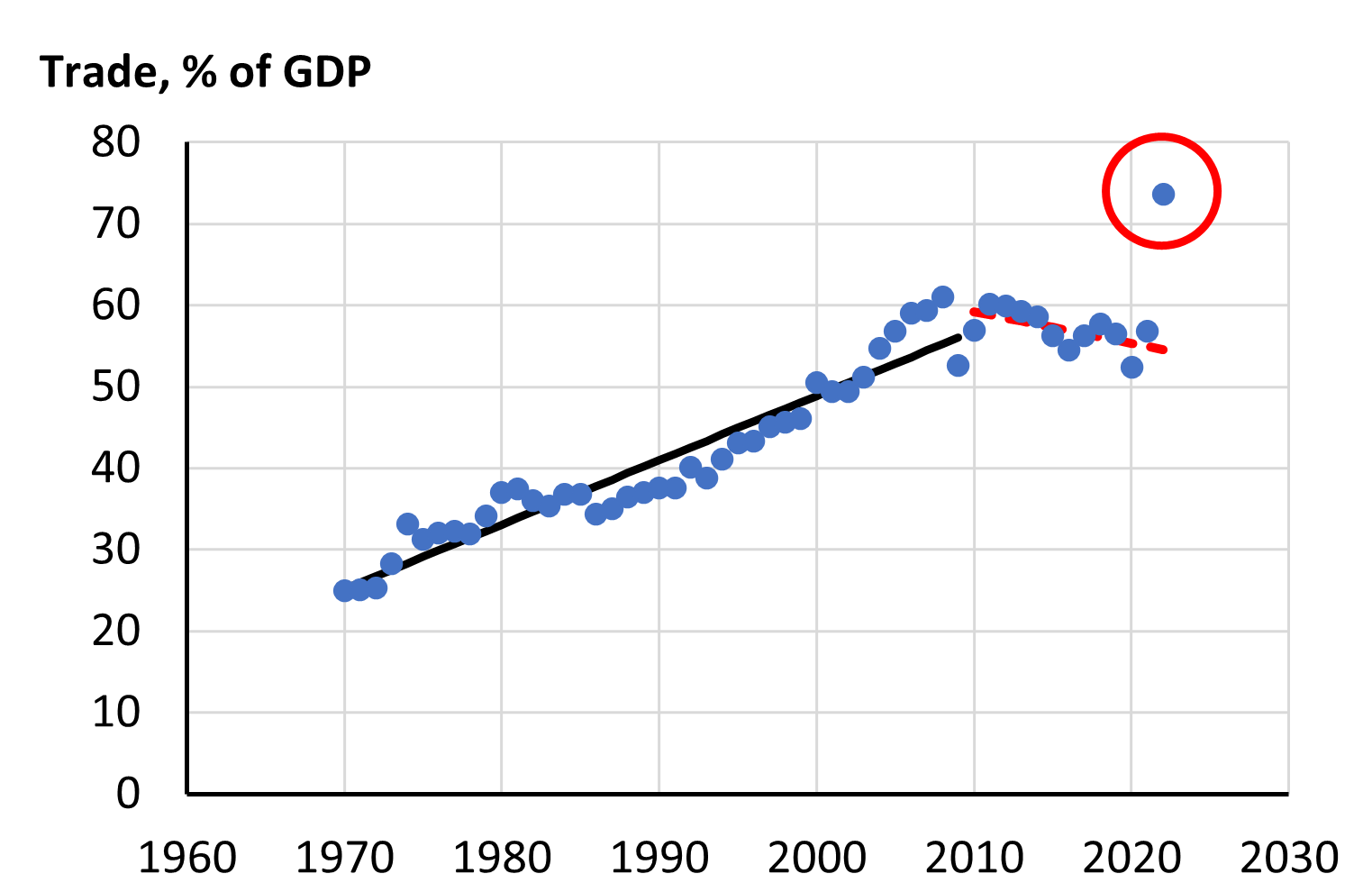

We live in a time when grabbing data at the source is incredibly easy. This is World Bank data on Trade as a percent of World GDP. I made the chart so the trendlines and circle on the 2022 data point I added.

This model of global trade fascinates me. It provides insight and raises questions at the same time. I love the inference that since the trade alliances were forged after WW II, the global community has been investing in trade increasingly as the value of final goods and services (GDP) of all the countries added up. Until the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. The last dozen years or so, according to this data, there has been a pause, a drop from 60 percent of world GDP, down to trade as 50 percent of GDP. While that is still a high level of trade, it has not been ramping up as it did consistently for 60 years. This seems to indicate, the world and all of its domestic economies and governments are making local transactions a priority.

And then the questions begin…

- Pulling the data for this post, the level of trade as a percent of GDP for 2022 is at nearly 75 percent. What is this about? Do all the inflationary costs of 2022 exaggerate everything prior? Do the shortages caused by the war in eastern Europe (clear disruption in trade of energy, grain, but not high valued weapons) actually indicate trade is advancing?

- Is Trade (sum of imports and exports) the correct measure? Details like a country that mostly exports, and another country mostly imports get lost in the trade metric.

- The trade as a percent of GDP is a relative measure and creates and index of change rather than focusing on the absolute values like ($US). But it does not show which individual economies are growing and which are not, or which countries are trading more and which are trading less. Does the cumulative output of 200 nations in a post-pandemic world function sufficiently different than the last 75 years, indicate the need to look for a different economic indicator?

Teaching undergraduate economics and agribusiness the last 7 years, has made me a passionate believer in local markets and economies. They only work when the conditions are right, but for things in rural areas like bioenergy, livestock feeding operations, and local food; it is not random. In 2001 on September 11th, the US embarked on a significant campaign to become less dependent on foreign oil. The US economy and politics were in harmony long enough to put into motion a 20-year expansion of alternative energy infrastructures. Like everything political, there are at least two sides. And the difficulty in moving forward is due to the reality that both sides have merit.

As mentioned in my first post this year, it has taken 50 years to begin to pay down the environmental externalities of the 1970s, but the investments and sacrifice are beginning to show up in benefits.

Better understanding of local markets is part of that change.

Comments

Local, the Uneasy Substitute to Global — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>