Making Sense of Retail Food Through Coffee

Food is as old as dirt. However, in 2024 the word ‘food’ is poorly understood. Pandemics, supply-chain challenges, trade wars, real wars; have all contributed to growing concern about access to food. Clarifying and aligning definitions of food will take many steps.

A starting point in describing food is as the final use of products eaten for nutrition. In economic terms, food is the retail delivery of nutrients for human consumption. This is intentionally broad, but does not include agricultural commodities, intermediate valued wholesale food, or food waste. For our purposes food is the final form in which human nutrients are eaten and consumed.

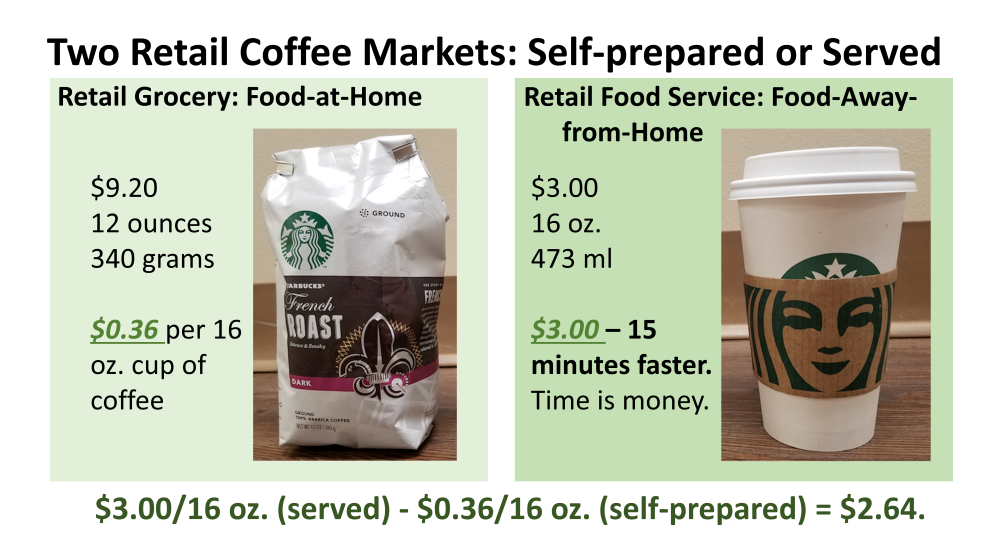

USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) defines the retail food sector, conveniently in two subsets of food-at-home and food-away-from-home. Food-at-home is food products sold at grocery stores that require preparation at home. Food-away-from-home included restaurants, but it also includes institutional food like school cafeterias. Food-away-from-home is food that is served.

On August 23, 2024, the ERS released their Food Price Outlook. Overall, food prices increased by 2.2 percent since July 2023. But by breaking it into subcategories of food-at-home and food-away-from-home, useful differences emerge. In July 2024, the food-at-home (grocery purchases) CPI increased by 1.1 percent from July 2023. The food-away-from-home (restaurant purchases) CPI increased by 4.1 percent from July 2023. The overall price increase for the U.S. economy was 2.9 percent higher in the same period. In one sense food price increases are moderating all prices across the economy. But grocery store prices (food-at-home) are moderating restaurant food prices.

This refinement of food markets into two subsets changes the story significantly.

The image in this post is from my early conversations about food with undergraduate students about seven years ago at Greenville University. Do-it-yourself, ground coffee from a retail grocery store compared to paying someone to prepare and serve coffee as retail restaurant food.

Ground coffee costs $0.36 for a 16-ounce cup of coffee; assuming the equipment, water, and energy to heat the water are negligible compared to the cost of coffee. The 12-ounce package of ground coffee in our example is $12 per pound. The high relative cost of coffee validates this simplifying assumption.

The same 16-ounce coffee, when prepared by someone else likely sells for $3.00. What rational consumer would pay nearly 10 times more for that convenience? I do. Frequently. If I am mobile in my car, making coffee is not very practical. Paying $3 for a coffee – versus going without – is rational. I also make a lot of my own coffee. $0.36 per cup is much greater value when it works out.

Subtracting the difference, $3.00 – $0.36 yields $2.64 differential. Assigning a 15-minute offset in time savings for paying someone to make the coffee provides working value of our coffee-making time of $0.18 per minute. The hourly value of our coffee making time is $10.54. Yes, this is a made-up number. If one arrives at the airport an hour before their flight and pays a higher airport premium price of $4 per cup, it is also likely worth it. [Note: $3/16 oz coffee x 8 coffees/gallon = $24/gallon for coffee. This compares to $3.50 for a gallon of milk or gasoline.]

Which brings us to the root of the problem. Why are restaurant food prices still going up?

The easy answer is because they can. Consumers are still willing to pay for it.

- Restauranteurs, including coffee stores, have gone through a period of wage increases driven by a shortage of workers. Service sectors carrying additional labor costs over grocery store/do-it-yourself food preparation.

- Even before the pandemic, food culture created premium pricing. Whole Foods redefined economic theory of a rational consumer by monetizing food attribute benefits that had not been traditionally recognized. This justified paying more than the least cost price. When the pandemic hit, consumers willingly paid an additional premium for comfort food. Grocery retail, or food-at-home, has already corrected for that shift. Restaurants are beginning to lose customers to more cost-effective food at home.

- U.S. coffee is imported. The food-at-home prices for coffee may be higher than the values ERS reported. Many imported goods have suffered increased import tariffs.

- Finally, there are food waste costs imbedded in prepared coffee that may not show up in grocery coffee. Only about 20 percent of the coffee in the bean goes into the coffee consumed in the cup. That means that every cup of coffee instantly has 80 percent food waste, 11 grams of used coffee grounds out of 13.5 grams of coffee. Byproduct management of coffee, and other food waste, will play a role in lowering food costs.

These are some of the drivers of higher food-away-from-home costs. In just a few paragraphs the drivers behind retail food prices are far more complicated than simply controlling the umbrella price of food.

One easy fix, finish the delayed farm bill legislation. For more than 90 years, farm bills have consistently kept U.S. food prices lower to the benefit of everyone. When food ingredient costs, or commodities, are lower, the retail prices are more likely to also be lower.

Comments

Making Sense of Retail Food Through Coffee — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>