Making Sen$e of the Calculus of Food Price Increases

Food price inflation is still in the news. Eggs have become a national security issue. Well, one would think so from the news. Mostly, the egg-laying chickens are sick and dying. But once we get beyond this egg-industry crisis, we will likely suffer from too many eggs for a bit. Locally, in downstate Illinois in late January 2025, on the same shopping day one grocery store had eggs for $2.99 per dozen, while the store down the street were selling eggs for $7.39 per dozen. Both stores were doing a healthy business.

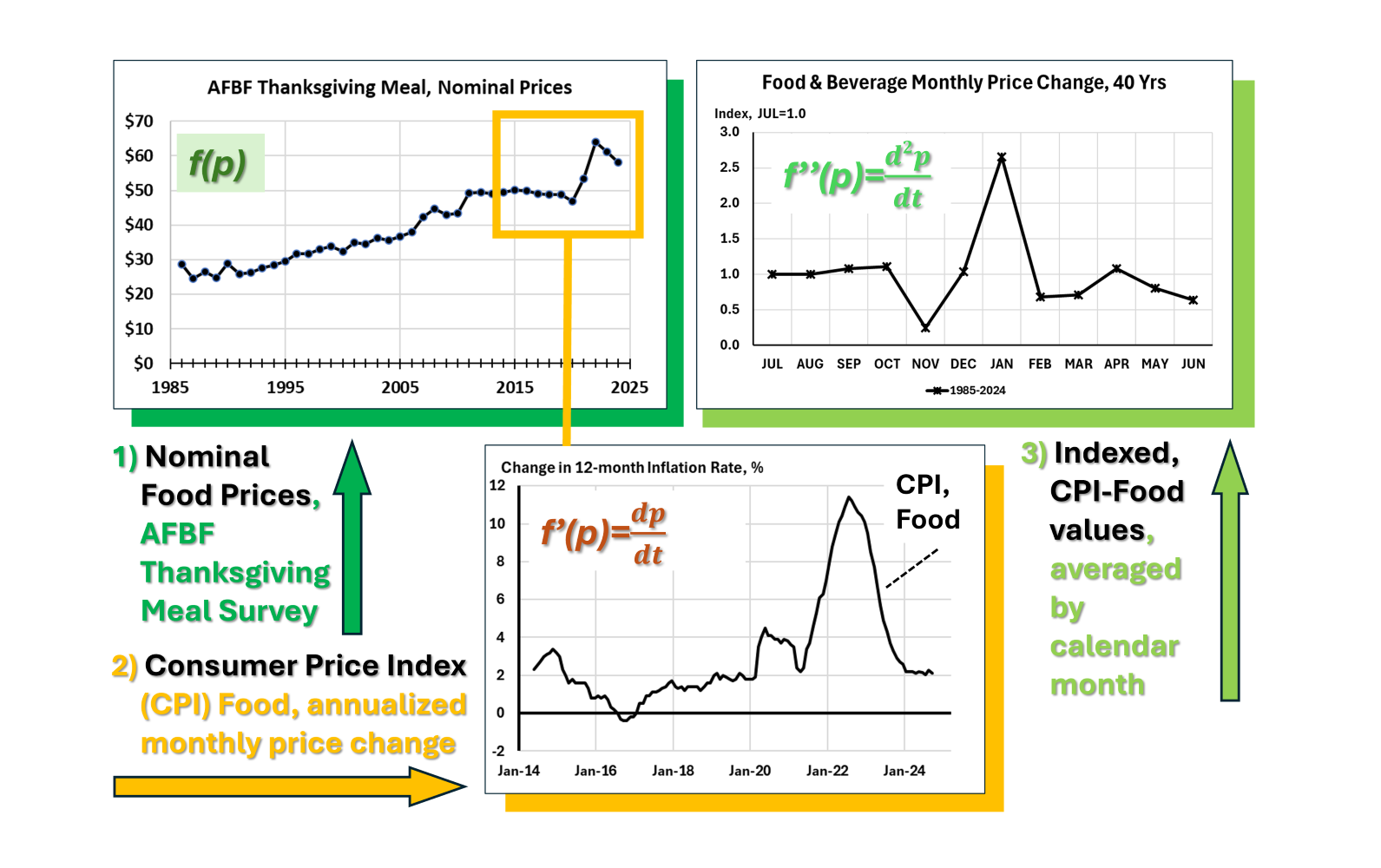

These three charts have all been posted on the Biomass Rules blog since November. They are all about food prices. Some similarities can be seen, but the right-most chart doesn’t really align with the other two charts. This is an opportunity to explain these 3 food price charts.

- The ‘Nominal Food Prices‘ chart is from, Deriving Real Values for AFBF’s Thanksgiving Survey – What The Function, November 26, 2024. This data is simply prices paid in dollars for food items in November across the country. The American Farm Bureau Federation members collect these prices every November and they are not adjusted for inflation. In the original chart posted in November there was also the inflation adjusted prices (real prices). The ‘What the Function’ part described the relationships to deflate the reported prices.

- The ‘Consumer Price Index‘ chart is from, Food Prices are Not Driving 2024 Inflation – Real Adventures in Economics, on November 14, 2024. The CPI is an index of prices. In this case it is an index of food prices. Food prices, like energy prices, go up and down, while all the prices except food and energy are fairly stable. Indices allow us to look at the relative, or incremental changes. This is a different lens than the absolute nominal prices. Absolute prices are no less important than relative prices, but both provide value. This presentation of monthly food CPI values provide a time series, or sequential, flow to the annualized, or 12-month change in food prices. The original chart in this post included food at home and food away from home. These two subcategories perform differently compared to inflationary price increases.

- The third chart, ‘Indexed, CPI-Food Values‘ is from, Buckle Up for the 40-Year Cycle of Year-End Food Price Rhythm, on January 22, 2205. Here the Consumer Price Index, food values (an index), are indexed again on the basis of individual changes between months. While the decrease in NOV, and the two successive increases in DEC and JAN, may resemble the peaks in the other two charts, this peak is much different.

Each of these charts represents a successive magnification of the changes in food prices. The Thanksgiving prices reported with transactions are the view available to the naked eye. We all buy food. This is the level that is most intuitive.

The second chart on the CPI-Food values is a figurative magnifying glass to look at the incremental change over time. It no longer looks at the cumulative, absolute change, but illustrates the marginal or incremental change from one time period to the next. The calculations are based on each leading month as they appear, but the previous 11 months are summed up to make 12 months of price changes. The change in inflation is reported for 12 months, but it changes each month. It isn’t really based on a calendar year.

The third chart takes the data from the magnified price data and looks at it under a higher magnification like a microscope. Here the incremental CPI is indexed to monthly price changes within the context of a calendar year. In this instance the calendar year begins in July, selected because it centered the big monthly changes in NOV, DEC, and JAN price indices, and it was not a violation of any theoretical principles. The original post broke the monthly changes into 4 individual decades. This chart aggregates 4o years of monthly price changes into a single value (line). The nine months from FEB to OCT are basically flat. Only in NOV, DEC, and JAN do the prices always move.

How does the consistency of these very focused monthly price changes compare with the reality of buying food in November that continues mostly upward. It is like looking at a very specific body part of an elephant like the trunk, or the ears, or the feed, that are all very different versus looking at the entire elephant, or perhaps, the elephant herd in the larger ecosystem. Each of these provides a valued perspective but they are different. Zooming in two levels identifies a persistent cycle, but the magnitude may not resemble the detailed cycle.

This happens with commodity prices. It can be shown with confidence that harvest time is the lowest price of the season when looking at month to month changes in the price of corn. But if prices are rising or declining on a larger scale through harvest, the highest price that crop year, may happen after harvest or before.

Zooming in to different levels of economic activity is what taking a derivative in calculus does for us. Indexing the nominal prices is similar to taking the first derivative. Indexing the index in the last chart is like taking a second derivative. Watching these changes in real time with my own numbers is more intuitive for me than the theoretical underpinning that allows us to understand these calculations.

Thirty years after graduate school the calculus of food prices is much clearer than while trying to pass the theoretical exams back then.

Comments

Making Sen$e of the Calculus of Food Price Increases — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>