Discovering Manure Value When Markets and CAFO Regulations Both Fail

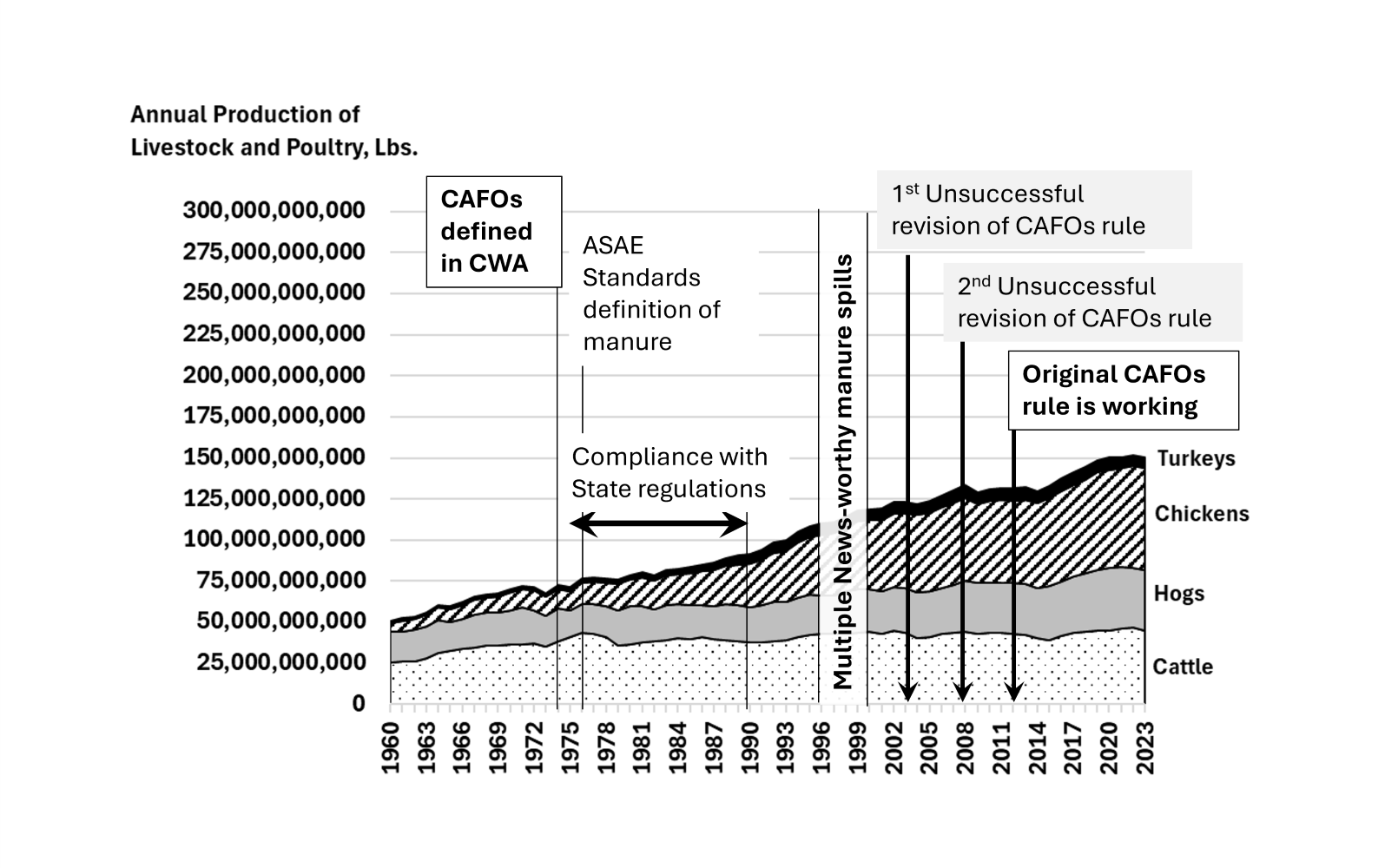

When markets fail to perform efficiently does that mean only a government policy fix will work? Or when the government policies fail does that mean only a market fix will succeed? In a word, no. This chart shows the total pounds of slaughtered cattle, hogs, chickens, and turkeys since 1960. The total pounds of meat produced has doubled since the Clean Water Act was signed in 1973.

The marketing framework for manure failed in the 1990s, in part, because manure was not marketed at that time. Manure had become undervalued and poorly managed. Enormous reservoirs of anaerobic effluent would occasionally break through their dams and overwhelm the countryside with millions of gallons of unstable fecal material. Not a fetching mental image, even less so in real life.

With the market failure externality, the handiest tool in the market policy toolbox is to regulate it. In the 1990s this task fell to the EPA. With the 1973 Clean Water Act, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) were defined based on a standard of 1,000 cows or more. Subsequently, large livestock facilities were regulated.

The federal law empowered the states to make it happen. And the states went to work to manage livestock operations by state, across the country. The rapid grow of livestock operation size was unforeseen at that time. There were not many farms in 1970 that would require a 7-acre anaerobic lagoon, but by the 1990s farms were getting large. Manure technologies for larger livestock facilities took a little longer to catch up.

The manure spills and nutrient management challenges of the 1990s got to a breaking point. Most nutrient water quality problems were directed to livestock as the problem, whether they happened in a concentrated human feeding operation – cities – or near livestock farms. But there were some manure science lessons to be learned also. First, it was more common to apply manure to the low concentration of nitrogen, ignoring the higher concentration of manure phosphorus. This resulted in very high levels of applied phosphorus. Second, it was not fully appreciated that phosphorus was present in a very mobile, liquid form in manure.

The EPA stepped in and blamed the states for dropping their responsibilities. The EPA did a first-ever, inventory of manure produced in the United States. Like all seminal inventories of this nature, it was a bit naïve. But it was actually a very reasonable thing to do. And like all inventories of this nature, they get better with practice.

In 2003 the EPA came out with their Final CAFO rule. It was tested in federal court. In a stroke of uneasy providence, the farming community who felt the EPA overreached its authority and the environmental community who felt the EPA did not exercise sufficient authority became teammates. The federal court about EPA’s lawsuits said we are only going to do this one time, so the farming community and the environmental community joined forces. The fallout was the court struck down the EPA CAFO rule.

In 2008, the entire cycle repeated itself. EPA released a revised CAFO rule. It went to court. Farmers and environmental advocates joined forces for the same reasons as in 2003. The federal court struck down the 2008 CAFO rule.

In 2012, the EPA issued a third CAFO rule that effectively said we are done with this. The existing regulatory infrastructure is working better than initially viewed.

So the manure market failure was followed by a documented government failure, of sorts. The federal attempt to strengthen restrictions around farm-raised manure failed. But the initial infrastructure empowering states to oversee livestock operations was working pretty well.

That is not the end of the story. Even though the buildup of organic nutrient leftovers (manure) reached and exceeded economic and environmental system capacities, or market failure. And the federal government tried to fix it unsuccessfully with stronger Clean Water Act regulations, or government failure. The livestock industry came to the table and found solutions.

- In 2005, the ASAE (now ASABE) updated their standards on Manure Production and Characteristics. Prior to this the last update was in the 1970s. Over those 30 years, genetics had improved and feed efficiency in gains had increased significantly. Animals were gaining more per pound of feed and excreting less.

- Animal scientists and feed managers realized they could formulate livestock feeds on available phosphorus rather than available phosphorus. This reduced the amount of phosphorus in the feed rations and subsequently reduced the phosphorus levels excreted in manure.

- The manure support industries got better. Liquid manure handling systems became more efficient and cost effective. Layer operations removed both the water and bedding to produce a dry manure product. Anaerobic digesters came into their own after decades of trial and error.

While some manure producers did underestimate the attention necessary to manage manure in the 1990s, creating a manure market failure. And the federal government unsuccessfully attempted to impose greater restrictions on manure producers creating a government failure. The livestock industry and support industries figured it out and brought the manure externality – that had slipped outside the system of the 1990s – back into the functional economy. The private correction was far more efficient than the new CAFO rules would have been.

Today, manure is an integral part of success in livestock production systems. Great job, everyone! Biomass rules!

Comments

Discovering Manure Value When Markets and CAFO Regulations Both Fail — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>