Hidden Benefits of Declining Hog Pastures

The United States is losing farmland but productivity and output continue to increase. Last week, the loss of 11 million acres of pastureland to cropland was explored. That blog also examined the over emphasized claims on cattle as an environmental challenge. Shifts in U.S. hog production have facilitated gains from lost pastures, but getting hogs off the pastures was a good thing for the environment, as well as the welfare of the pigs.

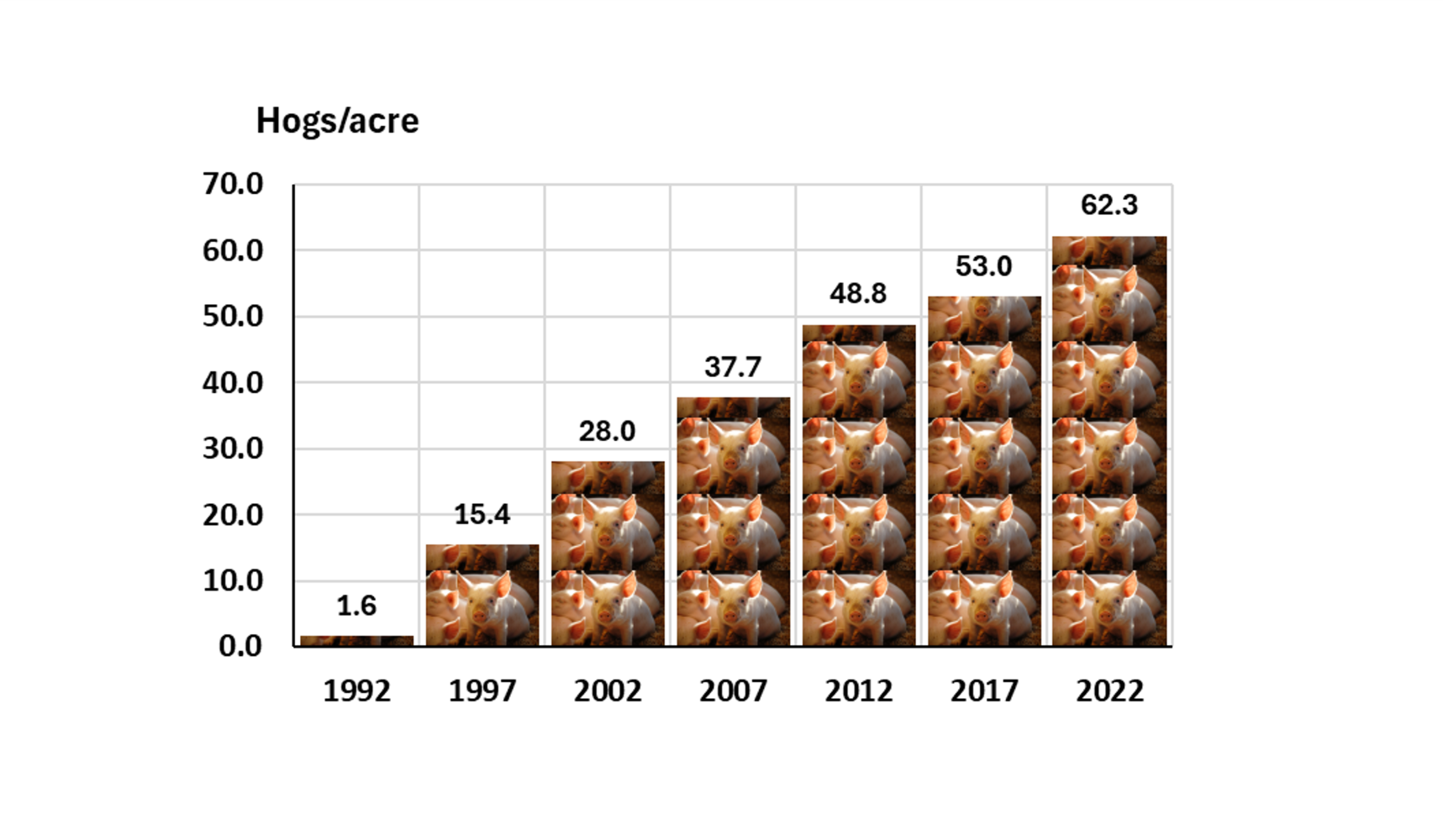

It is difficult not to think of acres as farm size. It is easy for crops anyway to think of 500 acre of corn being smaller than 5,000 acres of corn. There was a time when that worked for livestock also, but today not so much. This bar chart today shows the increasing pigs per acre since 1992. These numbers were estimated using the Census of Agriculture table on industrial classifications, North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). Hog farms have an NAICS number. The NAICS number for hog and pig farming is 1122. The 2022 Census of Ag Summary of farms by NAICS number is Table 75, Volume 1.

Going back to 1992, the hogs and pig inventory and sales were summed in each census, as well as the acres of cropland, pastureland, and woodland. There were a few adjustments made. The NAICS system wasn’t in place the entire time and in 1992, the Census of Agriculture didn’t have a hog-specific industrial code. This metric is for illustrative purposes. If the land on which hog farms raise hogs is declining, but that has not thwarted hog production, there must be reason. This chart shows that the density of hogs per farm, head per acre, has increased continuously since 1992.

The interesting thing is the USDA conservation policies aligned well with the transition of hogs from pastures to indoor pens. In the 1985 Farm Bill, one of the new provisions was the type of land classified as Highly Erodible Land (HEL) required a management strategy as part of the farm’s conservation plan. There is a lot in that sentence.

- Highly Erodible Land is land has a specific definition that is too technical to be helpful, but effectively it slope and does not have much topsoil. Sloping land that is not very productive, but it does well with permanent pastures.

- The USDA Conservation Plan is a document that is required to participate in the USDA conservation plans. But in 1985, the plan became linked to any kind of federal farm payments. So if a farm participated in commodity payments, it had to have an accurate conservation plan (approved by the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) on file with the USDA, Farm Services Agency (FSA).

The opportunity to enroll millions of acres of hog pastures into the Conservation Reserve Program as hog buildings became the predominant practice was an excellent policy assist. Recall that the late 1970s and 1980s were difficult financially for farms. High interest rates and land prices made that time difficult for everyone.

Hogs on pastures are not the same environmental impact as cattle on pastures. Hogs like to root in the dirt and it is very easy so have significant erosion on even the best managed hog pastures. Soil loss was the first farm emission of concern. The Dust Bowl of the 1930’s where topsoil became air born and moved cross country created an erosion crisis that is still being managed 90 years later.

But the 1985 farm bill conservation provisions were part of that soil erosion control priority fifty years later. It worked famously. Since that time we have moved our environmental metrics from soil loss to nitrogen loss, phosphorus loss, manure in water ways, odors, and greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide).

This post is not the forum, but as a hog farmer with experience in both pasture hogs and confined hogs (indoors). The confined buildings would be my management choice every time. In the 1960s there were many undervalued/underutilized pasture acres. Putting hogs on them was a way to make them more profitable. As a pasture hog farmer, maintaining running water 12 months of the year was always a challenge, and predator losses particularly during farrowing (baby pigs arriving). Breeding/Farrowing seasons were twice per year rather than continuously each month. Working the animals in corrals and sorting pens were pretty intrusive.

Management of pigs indoors changed everything, nearly always to the increased welfare of the animals. Better feed, better water, better health, zero predators, almost no handling stress for the animals. There are many who don’t see the animal benefits of indoor production. But what those outside of the farming community fail to see is the passion that farm families have for the welfare of their animals. Animals under authentic stress do not eat and grow. But this is likely a topic for a later post.

The lesson here is that the loss of pastureland to cropland – fewer acres in production – is not a story of decline. Hogs have increased their density per acre by moving to indoor production facilities. This has reduced significant farm erosion and increased productivity. The most obvious answers are usually not the most authentic story.

Comments

Hidden Benefits of Declining Hog Pastures — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>