Tracking Pastureland Use Change in USDA, Natural Resource Inventory

Land use change has gotten complicated. Tracking changes in climate have added more than simply physical changes in land use. The first step in understanding the more sophisticated land use change implications is to understand what land is changing. The go-to resource for this is the USDA, Natural Resources Inventory (NRI) Report.

A few weeks ago, the commercial biogas community was excited about a newly released report that identified potential new sources of biogas and the threat of unchecked methane emissions. The report on biogas potential referred to a justification from methane leakage from cows. That, folks, is a worn-out Biomass Rules’ ‘button’. While it is a reality that cattle do leak methane, that leakage, at least in the United States, is not ruining the planet as portrayed.

There are lots of reasons why bovine methane is not the most egregious climate villain. Initially it was surprising that cattle emitted methane in significant amounts. This is why we take inventories and conduct life cycle assessments (LCA). After the surprise, that information is a little misplaced.

For one thing, cattle-generated methane is created from carbon already in the atmosphere. This methane from ambient carbon is not liberated after being buried for millions of years as is leakage from fossil natural gas.

Deer, elk, and other ruminant wildlife also suffer the same methane leakage. We don’t count that because they are wildlife. However, cattle, sheep, goats, domesticated ruminants, arguably play a vital role in utilizing acres that cannot and should not be cultivated as cropland. Biomass Rules has skin in this game with academic training and experience in agronomy, anaerobic digestion, change in farming practices over time, and grazing management.

In addition to leaking methane from ambient carbon, domestic ruminants like cattle eat things that do not compete with human food sources, like grass. Grasslands differ from cropland. In fact, pastureland, rangeland, and grasslands all have different definitions. The USDA, Census of Agriculture also defines categories of cropland pastures, woodland pastures, and pastures that are not cropland or woodland. It pays to go deep.

The climate threat overlooked by focusing on the easy leakage from cattle is that revenue from grazing livestock provides a strong incentive to keep the more sensitive grazing lands in grass and other CO2 mitigating forms. When grain prices increased about a dozen years ago, some marginal lands that were doing well as pastures, were converted to cropland. It is possible to plow up sensitive lands and plant grains to them. They do not produce like prime cropland, and they erode rapidly. It is possible to do it, but a costly, bad idea.

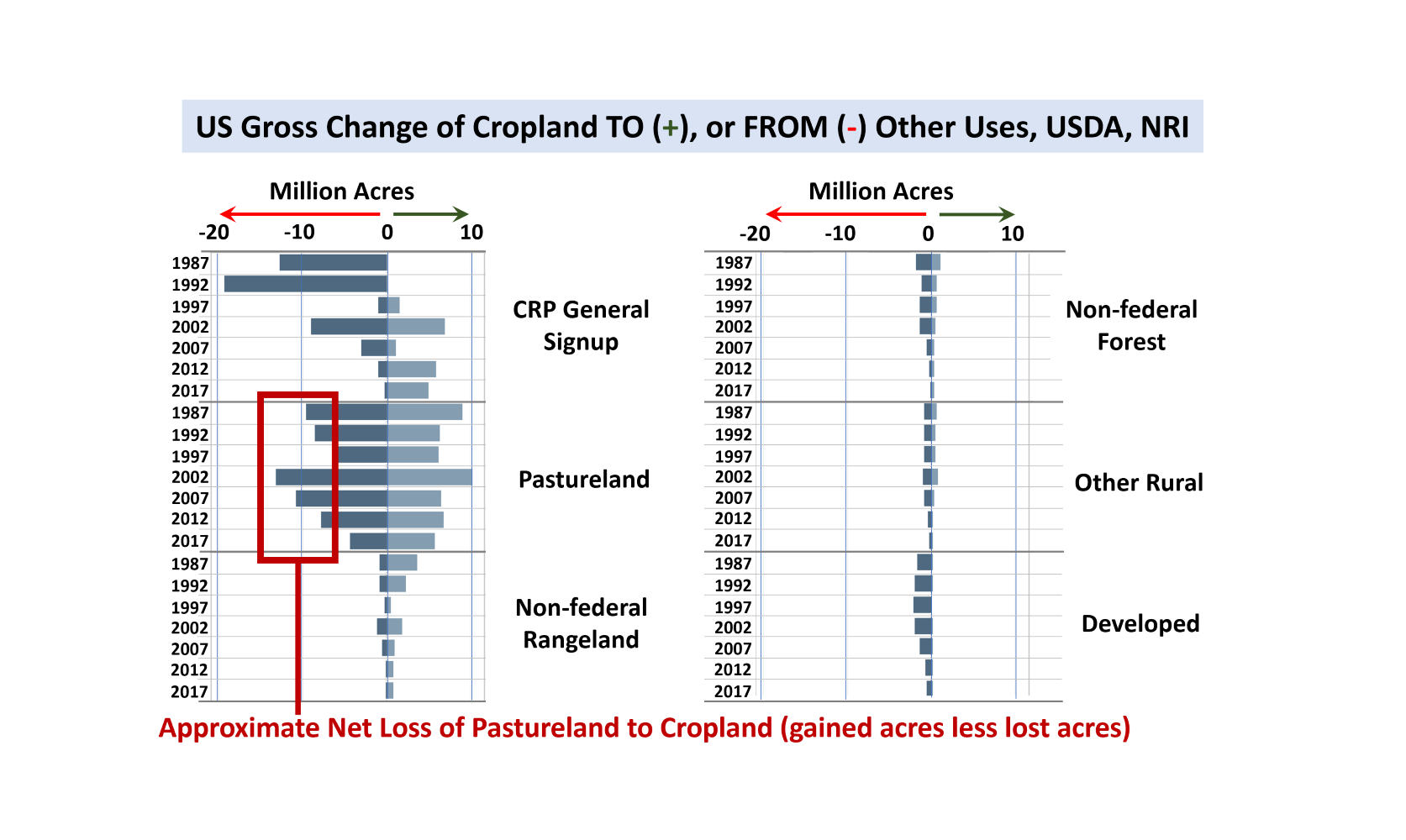

Which brings us to today’s chart, 35 years of US land use change in the NRI. This chart is from the NRI data visualization page. It was reformatted for our purposes but is really USDA’s from the Land Use Change page.

The reason this chart is included today is it shows that pastureland and cropland move back and forth more than any other land use type presented by the NRI. Cropland does not show up directly in this presentation. For pastureland, the positive increases were cropland that was changed to pasture. The negative values reflect pastureland that was lost to cropland. How can cropland be both lost and gained at the same time? An excellent question.

The NRI is conducted every 5 years and covers the entire United States. In the early years, the results were presented at the county-level, but funding cuts over time changed the sampling pool and reduced the granularity of the available data. Each year in the chart represents the end of each 5-year period. The NRI is still reported by state. There are states in which cropland became pastureland (positive acres). And states where pastureland became cropland (negative acres).

In the 35 years the NRI has been looking at changes in land use in the United States, a cumulative 11 million acres have moved from pastureland to cropland. Moving from grazing use of perennial pastures to tilling marginal cropland moves the climate challenge from methane gas emissions from cattle to nitrous oxide emissions from tilling soil. While methane gas is about 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide is nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Nitrous oxide is 12 times more potent than methane. In the last 35 years, 11 million acres of pastureland has been opened to cultivation and a release of nitrous oxide.

These absolute values, 25 times or 300 times worse, are not the metric of concern. There are tradeoffs. Biomass Rules is pro growing everything. If marginal lands (hilly and less productive) are pulled out of perennial ground cover to grow annual tilled crops, there are risks involved.

Cows play an active role in optimizing our carbon emissions and providing healthy ecosystems and food that we cannot produce on tillable cropland. There is good work being done on mitigating methane emissions from cattle in the United States. One of the amazing numbers is how much lower US methane emissions from cattle are relative to prior decades. The other complication from the earlier mentioned potential methane from anaerobic digesters report, it mixed global methane emissions to support US commercial biogas production. Cattle methane emissions in the US are lower due to the more efficient production systems. Global methane emissions from cattle are different than US methane emissions from cattle. Don’t mix the two sources in the Biomass Rules space or suffer the consequences of rebuttal.

This NRI is confusing to present and digest. Loss of cropland to the conservation reserve program (CRP) signup, is likely a good thing. Loss of cropland (again 11 million acres) to developed land use (cities and roads) is more concerning.

The National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), another USDA agency reports that farmland in the United States is declining, but this is not as critical as it may sound. We continue to move our land-based crops and livestock inside, so we are still producing more output on fewer acres. But let’s all try to rely a little less on using cattle as the scapegoat for climate challenges, please.

Comments

Tracking Pastureland Use Change in USDA, Natural Resource Inventory — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>